If you believe a knife is merely a tool for slicing bread or chopping an onion, chances are you’ve never held a true Hōchō (Japanese knife). In the West, we are accustomed to heavy, “indestructible” European blades—tools designed to hack through meat and, in a pinch, pry open a tin can. But in Japan, the philosophy is the polar opposite. Here, a knife is not just an object; it is an extension of the hand. This isn’t merely a user guide; it is a journey through history, metallurgy, and philosophy that explains why the world’s best chefs feel helpless without these instruments.

From Katana to Kitchen Knife

The DNA of the Japanese knife is inextricably linked to the samurai sword, yet the turning point in its evolution occurred not on the battlefield, but through politics. It all began in the 16th century in Sakai, a city renowned for gunsmithing. Until then, kitchen knives were seen as simple tools with no remarkable qualities. History took an unexpected turn with the arrival of the Portuguese and the introduction of tobacco. To shred tobacco leaves, a need arose for extremely sharp and precise tools. Sakai blacksmiths, spotting a new market, adapted katana manufacturing techniques to these small “tobacco knives.” This was the first step toward the kitchen. However, the true explosion occurred in the late 19th century, during the Meiji Restoration, with the passing of the Haitōrei Edict. This law banned samurai from carrying swords in public, leaving thousands of the country’s best smiths suddenly unemployed. To survive, they transferred their mastery and the “warrior’s spirit” philosophy to household tools. Thus, the legendary Japanese kitchen knife—possessing the soul of a katana—was born.

The DNA of the Japanese knife is inextricably linked to the samurai sword, yet the turning point in its evolution occurred not on the battlefield, but through politics. It all began in the 16th century in Sakai, a city renowned for gunsmithing. Until then, kitchen knives were seen as simple tools with no remarkable qualities. History took an unexpected turn with the arrival of the Portuguese and the introduction of tobacco. To shred tobacco leaves, a need arose for extremely sharp and precise tools. Sakai blacksmiths, spotting a new market, adapted katana manufacturing techniques to these small “tobacco knives.” This was the first step toward the kitchen. However, the true explosion occurred in the late 19th century, during the Meiji Restoration, with the passing of the Haitōrei Edict. This law banned samurai from carrying swords in public, leaving thousands of the country’s best smiths suddenly unemployed. To survive, they transferred their mastery and the “warrior’s spirit” philosophy to household tools. Thus, the legendary Japanese kitchen knife—possessing the soul of a katana—was born.

The Relentless Pursuit of Sharpness

In the West, we simply say a knife is “sharp,” but the Japanese use the term Kireaji (切れ味), which literally translates to “the taste of the cut.” This is not just a poetic metaphor; it is a law of physics. A dull knife acts like a wedge. It crushes cells, squeezing out juices and destroying texture. By contrast, a sharp Japanese knife acts like a scalpel. It severs the cell wall without damaging it. The result is evident on the plate: a piece of sashimi retains its natural umami (うま味)—that rich, deep savoriness that gives a dish body and highlights other flavors. In Japan, sharpness is considered an ingredient equal to salt or pepper, and experienced chefs will attest that a precise cut is essential for a dish’s presentation.

Wabi-Sabi Aesthetics and the Beauty of Imperfection

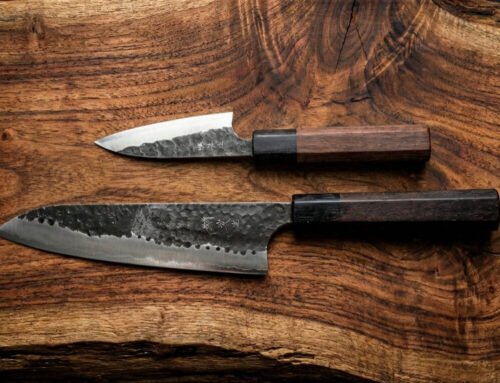

A Japanese knife—Hōchō—differs from its Western counterpart in appearance as well. It is dominated by the aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi, which exalts beauty in imperfection and naturalness. Many high-end knives, such as those forged by Echizen masters like Anryu or Yoshimi Kato, are not polished to a mirror shine. They are left with a Kurouchi, or “blacksmith’s finish.” This is the black, oxidized, rough part of the blade where hammer marks are still visible. It is a reminder that this object was created by a human in fire, not a robot in a factory. It is a tool that demands respect, for it is not designed for brute force, but for harmonious work.

A Japanese knife—Hōchō—differs from its Western counterpart in appearance as well. It is dominated by the aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi, which exalts beauty in imperfection and naturalness. Many high-end knives, such as those forged by Echizen masters like Anryu or Yoshimi Kato, are not polished to a mirror shine. They are left with a Kurouchi, or “blacksmith’s finish.” This is the black, oxidized, rough part of the blade where hammer marks are still visible. It is a reminder that this object was created by a human in fire, not a robot in a factory. It is a tool that demands respect, for it is not designed for brute force, but for harmonious work.

Innovation Born of Scarcity

One of the most interesting aspects of Japanese smithing is the San-mai (three layers), or “sandwich,” construction, which emerged from geological scarcity. Historically, Japan had very little high-quality iron ore, so masters could not afford to waste precious hard steel on the entire knife. They devised a brilliant solution: the core of the knife (Hagane) is made of extremely hard, expensive carbon steel, which forms the cutting edge. Meanwhile, this brittle core is “clad” on the sides with softer, cheaper, and more flexible rust-resistant steel (Jigane). This differs fundamentally from European knives, which are typically made from a single billet of softer metal. The Japanese method creates a knife with a core that is extremely hard and holds an edge for a long time, yet remains durable due to its soft outer shell.

A Sea of Shapes and Purposes

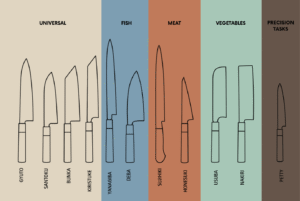

While the variety of Japanese knife shapes can be dizzying, each has a clear purpose. The equivalent of the Western chef’s knife is the Gyuto—the most versatile tool for meat, fish, and vegetables. However, in home kitchens, the Santoku reigns supreme; its name means “three virtues.” It is shorter, flatter, and incredibly comfortable for chopping. For vegetable lovers, the Nakiri, with its rectangular shape, allows for chopping without any “rocking” motion. The small Petty is used for delicate work, while the long and narrow Sujihiki is employed for slicing meat or fish in one long stroke. For those seeking distinctiveness, the Bunka, with its aggressive “K-tip” point, offers not just style but unparalleled precision.

For the beginner enthusiast, the temptation to buy a large set is strong, but unnecessary. You don’t need ten knives. To start, two faithful companions are quite enough. A Santoku or Bunka (about 165–180 mm long) will become your main tool for the majority of tasks, while a smaller Petty (120–150 mm) will handle precise tasks in hand or on the board. This duo covers the absolute majority of home kitchen needs and allows you to experience the true pleasure of Japanese cutting without a massive investment.

The Alchemy of Steel: From Living Metal to Powder

A knife’s character is defined by its heart—the steel. Here we encounter two main camps. Traditional carbon steel, known as “living metal,” is the choice for those seeking unrivaled sharpness. Shirogami (白紙鋼 — White Paper steel) is the purest, sharpest, and easiest to sharpen, but it is demanding—leave it wet, and it will rust quickly. Aogami (青紙鋼 — Blue Paper steel), with added tungsten and chromium, is slightly more durable and holds an edge longer. The other camp chooses modern stainless steels. The popular VG-10 offers excellent balance, but the real revolution lies in powdered steels like SG2 or R2. This is the “high-end” choice, combining extreme hardness with rust resistance. And for those seeking metallurgical miracles, ZDP-189 steel—masterfully handled by the Yoshida Hamono forge—reaches such hardness (HRC 67–68 out of 70) that holds an edge almost indefinitely, though sharpening it yourself is a true challenge.

Geometry, Sharpening, and Finish

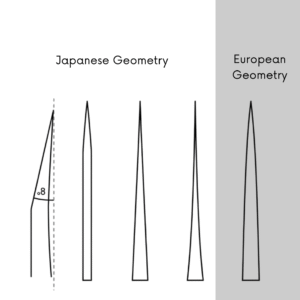

However, it is not just steel that determines the cut. Japanese knives are ground extremely thin, drastically reducing resistance when cutting dense products. Blades often feature a “Distal Taper”—they are thicker near the handle for strength and thin out toward the tip for precision. To maintain this delicate geometry, one must forget V-shaped pull-through sharpeners, which simply tear the metal. A Japanese knife demands water stones. Sharpening on a stone becomes a meditative process, allowing one to build a personal connection with the tool and control the extremely acute 10–15° angle.

However, it is not just steel that determines the cut. Japanese knives are ground extremely thin, drastically reducing resistance when cutting dense products. Blades often feature a “Distal Taper”—they are thicker near the handle for strength and thin out toward the tip for precision. To maintain this delicate geometry, one must forget V-shaped pull-through sharpeners, which simply tear the metal. A Japanese knife demands water stones. Sharpening on a stone becomes a meditative process, allowing one to build a personal connection with the tool and control the extremely acute 10–15° angle.

The blade surface is also not merely decoration. The aforementioned Kurouchi protects against rust, while Tsuchime—a hammered, dimpled surface—has a practical function: air pockets prevent products, like potatoes, from sticking to the blade. Nashiji, or “pear skin” finish, provides a pleasant texture, and the universally recognized Damascus pattern creates an aesthetic “rippling water” effect.

Handles: Where East Meets West

Finally, the soul of the knife is transmitted through the handle. Western Yo style handles are ergonomic and riveted, providing a sense of solidity. However, traditional Japanese Wa handles offer a completely different experience. Made from light wood—magnolia, walnut, or rosewood—they are fitted by driving the tang in. Their lightness shifts the center of balance forward, right into the blade. As a result, the knife feels sharper and more agile in the hand, truly becoming an extension of the arm.

Finally, the soul of the knife is transmitted through the handle. Western Yo style handles are ergonomic and riveted, providing a sense of solidity. However, traditional Japanese Wa handles offer a completely different experience. Made from light wood—magnolia, walnut, or rosewood—they are fitted by driving the tang in. Their lightness shifts the center of balance forward, right into the blade. As a result, the knife feels sharper and more agile in the hand, truly becoming an extension of the arm.

Why Invest in a Japanese Knife?

Acquiring a Japanese knife is not just a purchase—it is an investment in quality of life and experience. It changes the very process of cooking: you are not crushing food, but cutting it, preserving its texture and flavor. Work in the kitchen becomes a pleasure, not a chore. Furthermore, it is a touch of history. Holding a Japanese knife, you are touching a centuries-old tradition. Yes, a Japanese knife will require a change in habits—no dishwashers, no tossing it into the sink—but it will reward you a hundredfold every time you touch the cutting board.

The Collectible Value of Handmade Knives

Today, the value of handmade Japanese knives is rising rapidly, not only due to their quality but also because of low production volumes and unavoidable demographic shifts. The average age of traditional master bladesmiths in Japan is around 60, and the younger generation is increasingly reluctant to choose this arduous, physically exhausting craft that requires long years of apprenticeship and offers relatively low pay, even if its cultural prestige remains immense. Consequently, the ranks of masters thin every year, and authentic, handmade knives are becoming scarcer. Therefore, every such creation today is not just a top-tier kitchen tool, but an investment in a disappearing heritage—a tangible fragment of culture that will only become rarer in the future, and whose value, like other objects of true craftsmanship, will inevitably only grow.